Balkis-Island est une île fictive née de l’amitié entre l’architecte Yona Friedman et l’artiste Jean-Baptiste Decavèle. L’île a surgi dans la cartographie de l’imaginaire lors d’un concours de circonstances qui les a lié spontanément dans une collaboration artistique inattendue : la mort de Balkis, le chien adoré de Yona Friedman, et la redécouverte simultanée par Jean-Baptiste Decavèle d’images rapportées de ses voyages successifs sur les traces des grands explorateurs du Passage du Nord-Ouest, entre le Groenland et le Détroit de Béring.

Depuis toujours, l’image photographique cristallise la nécessité de se souvenir et le besoin de commémorer. Or, dix ans après son dernier voyage, en revoyant les photographies et les vidéos réalisées, Decavèle a été frappé par l’impression de vide et de distance qui émanent de l’absence de référents historiques donnant sens à ces lieux. Cette absence n’est pas uniquement due à un parti-pris du photographe, à une soi-disant objectivité, ou à l’oubli. Elle découle de l’étrange neutralité de ces paysages in situ.

Estimant ses documents comme étant des traces incomplètes et insatisfaisantes, car trop décontextualisés, une question liée à l’espace et au temps s’est ainsi posé : faut-il réinvestir ces lieux de mémoires collectives et individuelles tant contestés, et si oui, comment et pour qui ?

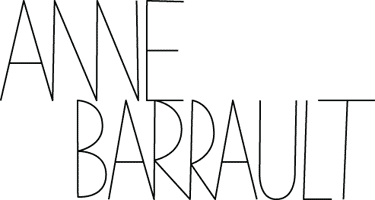

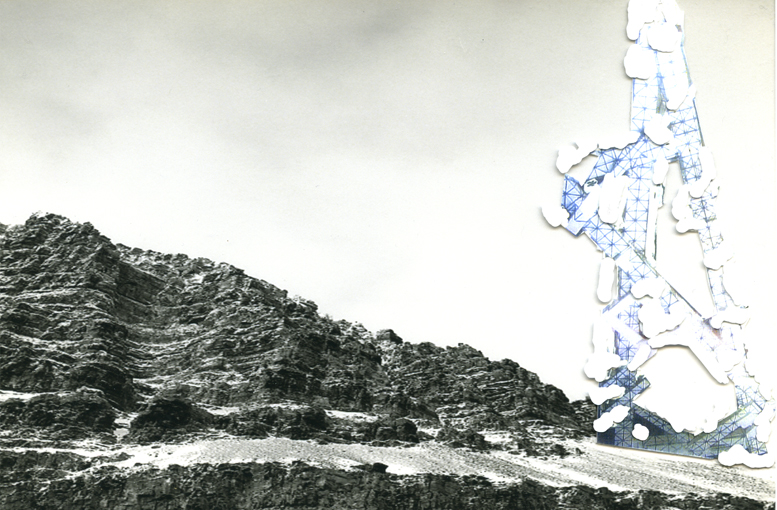

En hommage au chien défunt, Decavèle a donné le nom de Balkis-Island à cet ensemble, qu’il a ensuite offert à Yona Friedman. En réponse, Friedman s’est mis à envisager Balkis-Island comme une possible ‘ville-spatiale’, prolongement actuel de l’un de ses concepts phares. En apposant ses dessins sur rhodoïdes sur les photographies originales de Decavèle, Friedman a modifié une représentation privée et close en potentiel espace social de l’habitat, périodiquement habité, dans laquelle les structures architecturales se nichent dans les glaciers, se posent sur la toundra. Ce va-et-vient constant entre la représentation en images, le travail sur l’espace, et l’inscription de la mémoire est le principe structurant de l’existence même de Balkis-Island.

Présentées pour la première fois, la série des quarante-neuf œuvres de Friedman et Decavèle, les photographies de paysages non-transformées, et les deux vidéos de traversées vers Balkis-Island, sont le relevé initial d’un lieu en devenir, qui s’élabore à la dérive, s’amarrant à chaque fois en fonction de ses lieux d’attache.

_______________

Memorial for a Dog

Balkis-Island started as a joke. A friend of mine who participated in an exploration trip to the North Pole gave the name of my late dog Balkis, known for her literary activities, to an island at 78° latitude and 11° longitude.

Slowly the joke was turning more serious: My friend got an idea, that of ‘art at the Poles’. He gave me a lot of photographs of the island, and I thought to make photomontages of a ‘ville spatiale’ at the polar region.

But photomontages show only what can be visualized. So I got to think over an explanation of those pictures: how would work a city in the polar region? It presents a socio-ecological problem.

I would think about a city inhabited only 6 months per year the time span of the polar day. Sociologically a ‘summer-city’ is not as absurd; many vacation cities are crowded the summer and practically abandoned the winter.

A half-year city has interesting ecological properties. In this case, 6 months there is daylight. No artificial light is necessary; photo batteries could furnish electricity: many short-lived crops can be grown; protected in hot-houses (summer temperature at the poles does not exceed that of early spring in our latitudes).

Tower buildings could be reasonable because of the heat circulation: hot air rising toward the top, the lowest floors keeping cool: Probably hot-houses could be as well multi-level.

There must be protected communication between towers, protected against storms. Communicating bridges have to form a net, for security (as any of them can be damaged, a multiplicity of passages would be necessary.

If the towers are interconnected by bridges, they serve as well as bracing, increasing the wind resistance of the towers.

Extended flat buildings are not suited to the conditions, as both the roof and the ground are the major heat-loss surfaces.

The towers themselves can act as captors of sunlight, better than roofs, as the incidence angle is near to horizontal.

Portable wind-motors can be used to generate electricity too, but they can be easily damaged in harsh conditions.

The economic role of Balkis Island can become important with global warming: through the melting the polar shipping route becomes practicable, at least in summer. This fact increases the logics of a 6 months city: it could become a naval hub.

I agree that the idea of a Balkis-Port is a playful one. But it shows the realizability of a form of periodically inhabited habitat. As a larger part of our energy consumption comes from temperature conditioning of inhabited volumes, the period transport of residence from climate regions to other ones, could become the source of the most important energy saving programs we can already imagine.

Form follows function was an architect’s slogan in the 20th century. Towns follow seasons might be that of the 21st. It is a technique many animals (for example birds) practice. Why not humans?

Written the shortest day of 2007, in Paris.

Yona Friedman

Yona Friedman & Jean-Baptiste Decavèle

Balkis Island, 1996 – 2008

Tipp-Ex sur transparent et collage sur photographie

Yona Friedman & Jean-Baptiste Decavèle

Yona Friedman & Jean-Baptiste Decavèle

Balkis Island, 1996 – 2008

Tipp-Ex sur transparent et collage sur photographie

Yona Friedman & Jean-Baptiste Decavèle

Yona Friedman & Jean-Baptiste Decavèle

Balkis Island, 1996 – 2008

Tipp-Ex sur transparent et collage sur photographie

Yona Friedman & Jean-Baptiste Decavèle

Balkis Island, 1996 – 2008

Tipp-Ex sur transparent et collage sur photographie