Nothing in Alun Williams’s paintings is quite what it seems to be – or to put it more accurately, there is a lot more to everything than we might think at first acquaintance. Williams’s apparently straightforward recent works can seem to depend on the artist’s ability to invent wholly contemporary, engaging images – irresistible but unsentimental donkeys in a landscape, for example – and to exploit the physical expressiveness of his materials – roughly stroked paint on a coarse support or fluid ink on paper. But we soon become aware of the rigorous conceptual basis, at once deeply serious and playful, that informs these works. Williams comments on our present condition, in part by forcing those of us who pay attention to art to search our mental image banks, happily recognizing familiar works of art or struggling to retrieve obscure ones. What is it about that landscape background that seems familiar? Why do I feel that I’ve seen that setting not long ago? Isn’t that figure something I know from another context? In his most recent works, we are also forced to think about the ubiquitous media images of present day horrors.

That sense of fleeting familiarity is not an illusion. Williams deliberately rings changes on motifs from other works of art, as well as images of real places. It’s not appropriation but rather something closer to the way T.S. Eliot allowed his broad knowledge and appreciation of the literature of the past to resonate in his writing. Much of Williams’s earlier work was informed by scrupulous research into the history of locations he frequented or the neighborhoods of places where he exhibited or worked. He would discover a configuration – a paint stain or roadmark or inflection in a wall, among many other sources – that became a surrogate for a leading personage in the history. The configuration, now an autonomous character, was depicted in images based on the generating location, sometimes in the company of other characters in the story. Often, a related group of works would present several moments in the life of the protagonist, whom we learned to recognize in various settings.

Williams’ recent works are no less layered and allusive. They seem to have been stimulated equally by his knowledge of the history of art, especially modern art, and the disturbing state of our troubled world. The alarming news from the mid-east has been encapsulated by odalisques who appear to be refugees from the fictive North African Arcadia that Henri Matisse constructed with props and textiles in his Provençal studio. The newly energetic women gather in a group, armed with assault rifles, or sit amid the rubble in the aftermath of a bombing raid, subverting any lingering associations with an idealized world of idleness and pleasure. Donkeys, based on representations from artists as disparate at Franz Marc and Jean-Michel Basquiat, become ambassadors for everything from animal welfare, to brute labor, to endurance, to patience, at the same time that they remind us that they are symbols of the American Democratic party. In the apparently bucolic Crisis of Democracy #2 (Thomas Paine meets John Adams) (2023), two leading figures in the American Revolution, represented by dramatically different surrogates, shake hands in front of a New England house, watched by sympathetic donkeys.

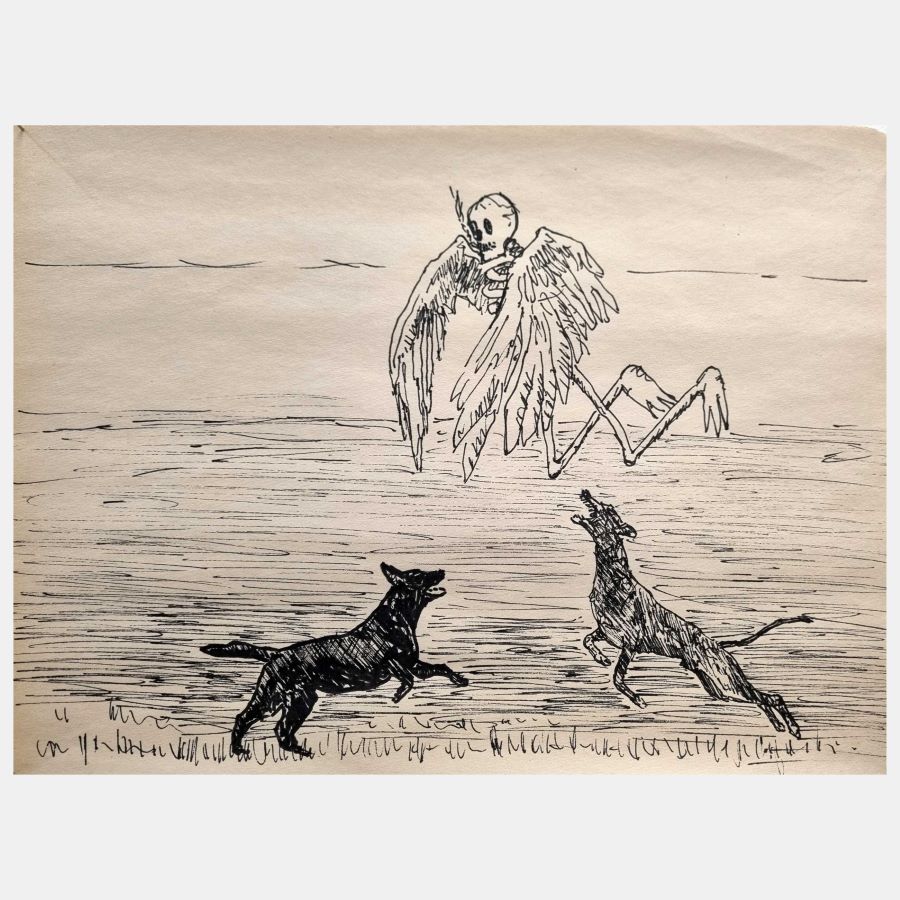

Elsewhere we find everything from elusive echoes to forthright reinventions of such wide-ranging sources as 17th century landscape painting and the work of John Constable, Vincent van Gogh, George Grosz, and Max Ernst, unified by Williams’s vigorous touch and evocative orchestration of hues. The images that serve as points of departure range from the familiar to the obscure. Whatever the starting point, Williams treats it with insouciance and invention, so that we are as engaged by his transformation of his sources as we are by recognizing or sensing the origin of the image. We are fascinated by the tension between the associations provoked by the usually benign source images and Williams’s insertions and alterations, which can range from personages from the art world to explosive suggestions of destruction. An allusion to a Constable landscape, for example, is almost overwhelmed by an image derived from recent media coverage of war. We are confronted by absorbing metaphors for the state of the world, perhaps even for the artist’s role in these troubled times as someone who bears witness, at the same that we are reminded, now overtly, now subliminally, of the long, enduring history of visual art. There’s no such ambiguity about the iterations of a jaunty, grotesque, cigarette-smoking Angel of War, conjured up in various material guises, at once sinister and bitterly funny. Once again, Williams has invented a memorable “character” who embodies complex meanings in a kind of visual shorthand, a potent emblem of our disturbing moment.

The art world, particularly the world of modernist icons, comes under scrutiny as well. Williams has updated Max Ernst’s Au Rendez-vous des Amis, his 1922 homage to nascent Surrealism. Painted two years before the publication of André Breton’s first manifesto defining the movement and named for a café, the large canvas presents portraits of fifteen of Ernst’s friends and colleagues, including Breton, Giorgio de Chirico, Louis Aragon, Paul Eluard, and his wife Gala, plus (presumably as precursors) Fyodor Dostoevsky and Raphael, as well as a self-portrait of the artist. Williams has substituted more recent pivotal figures in his version of the painting, New York Rendezvous: Joan Mitchell, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Mark Rothko, Edward Hopper, Marcel Duchamp, Barnett Newman, Roy Lichtenstein, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Louise Bourgeois, Jeff Koons, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, and Nancy Spero. Where possible, Williams has based his representations on extant self-portraits; where no prototype exists, as for Pollock, he has invented an image derived from the artist’s work. Paul Cézanne, standing in Dostoevsky, is derived from a portrait of the artist by Dan Flavin. If we make the effort to identify Williams’s characters, we begin to wonder about who was included and who omitted. Is this a personal pantheon? Was inclusion determined by chronology. We can only guess. Recent drawings, notable for both tonal subtlety and enlivening contrast, commemorate Jasper Johns’s, Robert Rauschenberg’s, and Cy Twombly’s visit to Robert Motherwell’s 1952 exhibition at Kootz Gallery or present an agile Louise Bourgeois at home.

Kenneth Noland, a painter notably absent from Williams’s overview of the recent New York art world, said that “When you look at a great painting, it’s like a conversation. It has questions for you. It raises questions in you.” Williams’s recent work certainly raises provocative questions. If we are attentive enough, it might even provide some answers.

Karen Wilkin

New York, October 2024

Karen Wilkin is an art critic, independent curator of modern and contemporary art, writer, teacher and art historian.

A close associate of Clement Greenberg from the 1970s until his death, she organized numerous museum exhibitions, often solo shows on artists such as Stuart Davis, David Smith, Anthony Caro, Helen Frankenthaler and Hans Hofmann. She has also curated numerous group shows exploring the nature of painting today, such as those in which she presented the work of Alun Williams in New York: The Body in Question at The Painting Center, (2021) and What only Paint can do at Triangle Gallery (2012).

Karen Wilkin is the author of several important monographs on the artists named above, as well as on others such as Paul Cézanne, Georges Braque, Giorgio Morandi and Kenneth Noland…

She writes regularly for : Art in America, The Wall Street Journal, The New Criterion, The Hudson Review et The Hopkins Review. She teaches at the New York Studio School.

ALUN WILLIAMS

Departure, 2024

acrylic on burlap

122 x 153 cm

exhibition view Art War & Democracy, Alun Williams, galerie anne barrault, 2024

(photo Aurélien Mole)

ALUN WILLIAMS

Arrival of war, 2024

acrylic on burlap

107 x 127 cm

exhibition view Art War & Democracy, Alun Williams, galerie anne barrault, 2024

(photo Aurélien Mole)

Alun Williams

Angel of war, 2024

black ink on paper

21,5 x 29 cm