Galerie anne barrault is delighted to present Lalitha Lajmi’s (1932-2023) first solo exhibition in France.

Born in Kolkata, India, her works are collected by the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bombay, the British Museum and the CSMVS Museum.

In 2023, a retrospective of her work was held at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bombay.

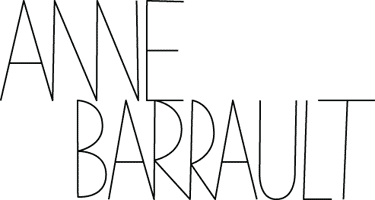

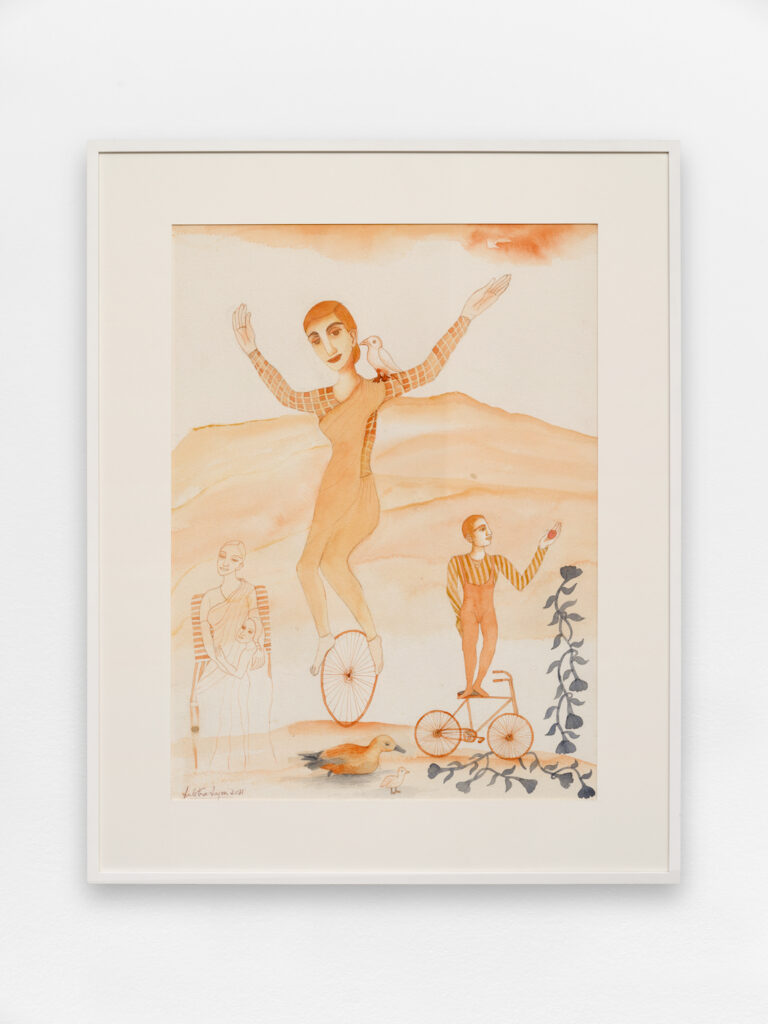

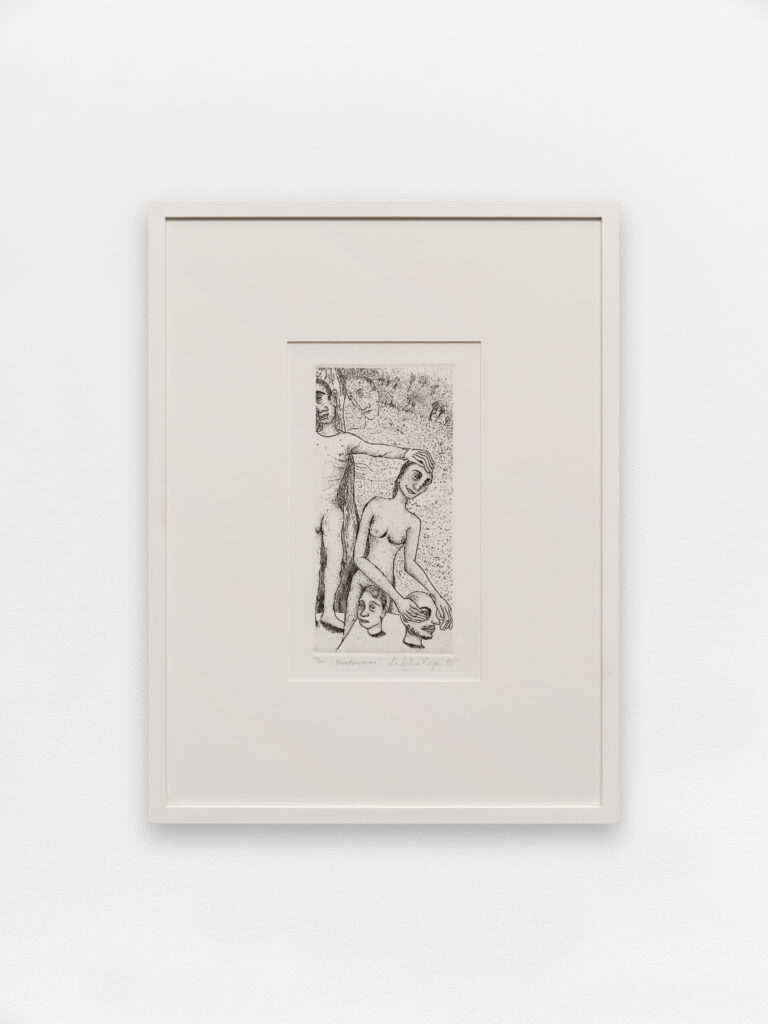

Lalitha Lajmi made herself the subject of her own work for nearly six decades. Her face is immediately identifiable in her self-portraiture, repeated tirelessly across hundreds of artworks: sleek and moonlike, chin angled upward, gaping, heavy-lidded eyes. Her body leaps from one painting to the next, sometimes surveying the scene, other times orchestrating it, always with the same self-aware smirk, her mouth pitched to one side. Her likeness is symbolic and archetypal, and she fastidiously reconstructs herself. Sometimes riding a unicycle, arms aloft, juggling orbs. Dancing, buoyant against blurry, uncanny landscapes. Standing at the front of the frame, palms open, a benevolent maestro.

She taught herself how to paint, etch, and make prints; she was productive, dedicated, and meticulous. Lajmi’s fixation on representing the self was, in fact, a national preoccupation during her time. She was a teenager when India was first formed as a republic independent from the British Empire. She was a young adult making art during a time of post-independence euphoria, when the project of Indian decolonization was underway. And there was work to be done. Mythologies had to be built, the nation-state given a new identity. The task at hand—taken up by politicians, historians, artists, writers, and filmmakers alike-was to fashion India a selfhood.

Lajmi’s artist contemporaries were actively recruited for the task—public commissions, murals, and photo-ops with politicians. The first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, enamored with European modernisms, flew in Le Corbusier to design a new city made of plump slabs of concrete. A group of raffish young men who called themselves the Bombay Progressive Artists were the stars of a new Indian modernism. Some painted idyllic village scenes with a wistful romanticism; others worked in abstraction, with oblique shapes representative of Indian traditions and histories. Feminine bodies appeared in modernists’ works as stylized nudes or as bodies of labor: farming, tending to domestic work. But Lajmi painted herself.

Lajmi began undergoing psychoanalysis in her thirties, and she obsessively wrote down her dreams. She was plainspoken about her interest in analysis; it was not just a matter of self-introspection but one of pursuing the addition of surreal interpretation onto her painterly plane. “It is natural for me to examine my dreams for shaping my images,” she said matter-of-factly in an interview with the Sunday Times in 1993. Psychoanalysis offered Lajmi a set of tools by which to dissolve the slim separation between reality and fiction, both in waking and sleeping life. It was in her watercolors, especially, that she worked through the materials of her dreams; the soft, slippery nature of the medium allowed her to be ambiguous and free flowing. “Dreams clarify things… longings are expressed,” she said.

Lajmi’s art offers a rich profusion of her inner world. The material produced by the psychoanalytic method is, by nature, elusive: recounting dreams that are fleeting in spirit; admitting to the desires and impulses forbidden by normative society; or trying to identify motivations so disguised we remain blind to them. In her dream journals, Lajmi writes lucidly about the knottiness of her dream life. She is obsessive, and even hubristic, and like with her painting, she plunders the recurrence of certain paranoias and yearnings. Of these, her sharpest glance is at the loneliness produced by the modern family unit; Lajmi herself had an arranged marriage.

Lajmi’s work is not just a reflection of her inner world but also a product of her circumstances. As an upper-caste woman from a Hindu family, she had the social mobility to shape her own identity. What makes her compelling is that she was obsessed with fashioning a selfhood in public, and staging archetypes while doing so. In making herself the primary subject of her work—informed by the era of Indian independence and modernity—she showed how the political project of modernity entered the interiority of the mind.

Contemporary India is a violent place, the roots of which were laid out at the time of India’s forming. It has become imperative to look back to move forward, return to this time of decolonization, and to take off the rose-colored glasses. To build other tellings of the early shaping of the Indian nation-state. In looking at the work and dreams of a woman who found herself in one center of this political, intellectual and cultural moment (as there were many of these apart from Bombay, spilling throughout the subcontinent), we enter a dialogue with her. Lajmi’s use of the materials of the psychoanalytic method to make her work lends itself to a reading of the modern subject as one that develops a self-reflexivity, that tests the limits of the mind. Lajmi’s inner world, of which she laid out the pieces for us to follow, affords something singular and extraordinary: her paintings and writings build an alternate history to the one most often told. Lajmi plainly admitted to her instinct toward keeping record: “Since I am a product of my time,” she said in the Sunday Express in 2023, “I don’t have the desire to produce timeless works. They too will have their place in history.”

At the center of this history are the fears, paranoias, and ambitions of a woman—a mother thrust into a world that was suddenly made modern. The self-styled figures in Lajmi’s paintings are desirous and full of mischief. They often appear as tricksters, chaos-makers the archetype that flits most between moralism, codes of conduct, and societal structures. The trickster has the sharpest intellect, and access to secret and hidden wisdom. The self is a representational economy, and to build selfhood was a modern concept. A narcissism slithers through Lajmi’s art and writings. It is of consequence. It is an intellectual project that unfolds the psychoanalytic method itself: turning the self into a prism through which we can enter society.

Skye Arundhati Thomas

Excerpted from Lalitha Lajmi by Skye Arundhati Thomas, imagine/otherwise series, copublished by Sternberg Press and artPost21, 2024.

Skye Arundhati Thomas is a writer and editor from India. Their new book Pleasure Gardens (co-written with Izabella Scott) on constitutional law and military occupation in Kashmir is out now with Mack Books, as is their third book, on the painter Lalitha Lajmi, with Sternberg Press. From 2021-24 they were co-editor of The White Review.

They are currently international curator-in-residence at the Fondation Pernod Ricard in Paris.

/////

Lalitha Lajmi’s book launch (Sternberg Press) at After 8 Books on May 21st at 7 PM

featuring a conversation with Françoise Vergès and Skye Arundhati Thomas.

_________________

Anne Barrault sincerely thanks Dev Lajmi and Skye Arundhati Thomas who have made it possible to present Lalitha Lajmi’s first solo exhibition in France.

Lalitha Lajmi

sans titre, 2018

série « Performer »

watercolour on paper

76,6 x 57,1 cm

courtesy of the Estate of Lalitha Lajmi and galerie anne barrault, Paris

Lalitha Lajmi

sans titre, 2011

watercolour on arch paper

76,7 x 57 cm

courtesy of the Estate of Lalitha Lajmi and galerie anne barrault, Paris

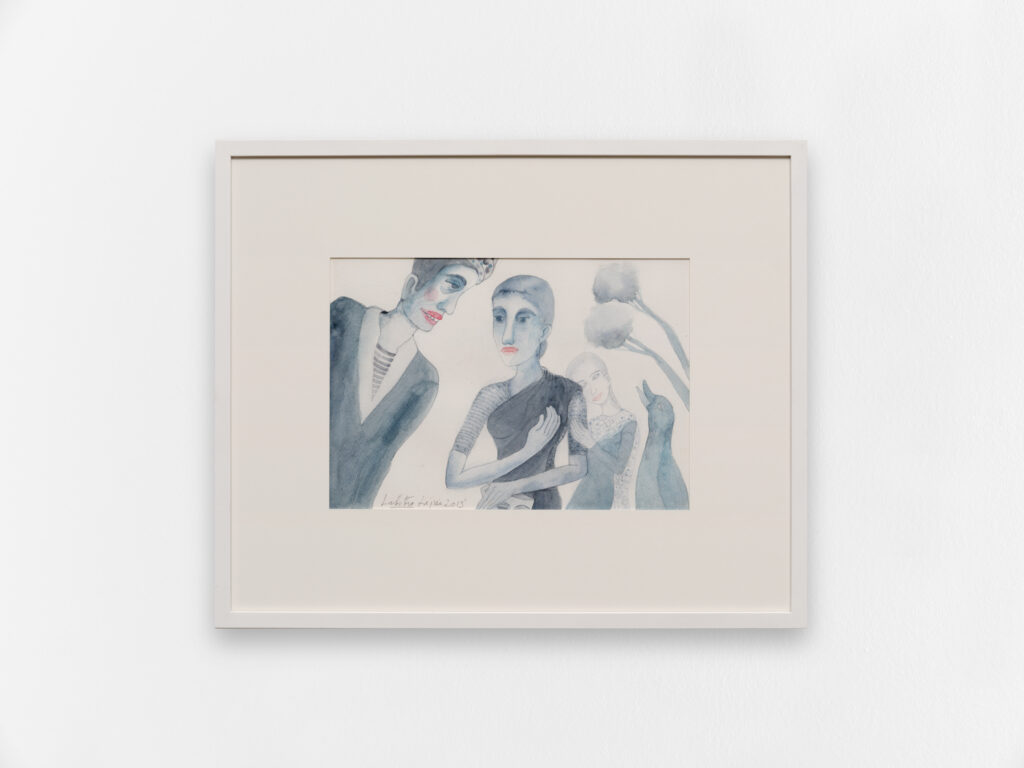

Lalitha Lajmi

Sans titre

watercolour on paper

25,5 x 35,6 cm / 46,5 x 56,5 cm ( avec cadre / framed )

courtesy of the Estate of Lalitha Lajmi and galerie anne barrault, Paris

Lalitha Lajmi

Performer, 1995

etching

49,6 x 34,8 cm / 53,2 x 40,1 cm ( avec cadre / framed )

courtesy of the Estate of Lalitha Lajmi and galerie anne barrault, Paris

Lalitha Lajmi

Sans titre, 2013

watercolour on paper

23 x 32,9 cm / 44,7 x 54,2 cm ( avec cadre / framed)