A few days before the opening of her exhibition at gallery anne barrault, Stéphanie Saadé, 35 years old, put an ad in the press. For this occasion, the artist wishes to gather 34 people her age (People Your Age), that is to say born, as she was on January 11th 1983. People, who, like her as well, will have lived 12786 days at this date of January 13th 2018. Difficult to know how these lives, beginning on the same day, will have previously met, moved away, bonded again, before this reunion in Paris. Literature or cinema would certainly be able to appropriate them and change this assembly into a sacred community, or assign it a remarkable destiny; but on this winter evening, rue des Archives, what does the complete matter of these lives incarnate if not an identical measure of time?

Those who are acquainted with the artist’s work know that her practice is largely crossed by the expression of physical or temporal distances; with People Your Age, Stéphanie Saadé thus tries to gather, without any certitude of succeeding however, a group of subjectivities marked by the same biological reality of an equal time of being in the world. “It is true that age has a particularity”, Tristan Garcia explains, “it is a category which not only separates people from each other (generations after generations), but also separates anyone from herself/himself in the course of time. Age seems like an identical natural movement for everyone, which carries us away ineluctably and takes us away from ourselves.”1 Beyond cultures, stories and experiences which divide as well as unite human trajectories, the estrangement of man from himself/herself which the essayist writes about appears as a universal component of the passing of time, as it is expressed by Stéphanie Saadé. This phenomenon is identified at different moments of the exhibition. In front of the nearly parallel lines framed under glass, precisely entitled Double Altitude, which indicate the height of the artist in two distinct situations: standing, or on tiptoes, in an attempt to prolong her growth artificially. On the floor where, gathered in a poor constellation, are spread the seeds and kernels of the fruits she has eaten since the last occurrence when this work was shown (Paradis en Cours). And also, in the perturbation of the familiar bounders of a school desk and chair, enhanced with brass tubes to make their height correspond to the standard height of adult furniture (The Shape of Distance). In these examples as well, it is not about a subjective appreciation of time, but about the measure, indeed the countdown, of what separates from a previous state. Thus, by avoiding the nostalgic pitfall and the sclerotic grip of pathos, the artist inscribes the flow of time in the dynamics of a resilient thought, constantly in movement. The memory apparatuses which she composes bear in them the potentiality of a time to come, like this lentil seed in the middle of a shallow dish which, wetted with a few drops, will grow slowly during the entire time of the exhibition, whereas the pure gold copy opposite it will remain frozen for ever. “ What potentiality aims at is reintroducing, into a saturated world, the amazement of something being born”2, Camille de Toledo suggests; the lentils of Contemplating an Old Memory express it too in their double temporality: the memory will find meaning only if the modalities of a becoming can be imagined for it.

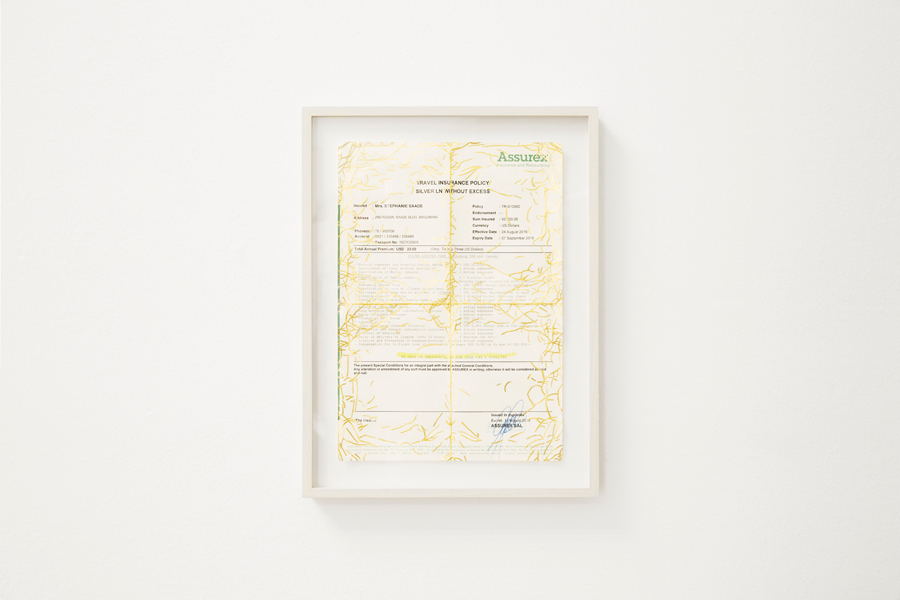

It would be difficult to tackle all these questions without evoking Stéphanie Saadé’s personnal story, whose childhood was concomitant with the civil war which destroyed Lebanon until the early 90s. One cannot help thinking also, when looking at the small weather vane on the facade of the gallery, about the events, which continue to shake the country and make it “lose North” anew, as one could say to extend the cardinal parallel with the title of the work (Pays à l’Ouest). To the work on time, which structures the artist’s practice, is added the work on space. However, the distinction could not be so strict as both intermingle and constitute together the poetics of distance towards which her work is constantly anchored. Then it is frequently about orientation, routes, actual displacements, whose lines are symbolically attributed to objects bearing the marks of their previous uses. There is a whole logic of deterritorialization: the extraction of something from its context, which leads it to find other echoes. One can once more wonder what a path taken to go to school (from which the work Aller à l’École takes its title) and copied out under the worn-out sole of children’s shoes figures, if not a simple sinuous line? Among the possible answers I am particularly interested in those which consist in saying it is about maintaining a permanence, a literally abstract one in an unstable country shaken by conflicts. The line which memorizes the windings is a mental projection toward a space whose existence is sanctuarized; the mother-of-pearl, which materializes it, and which the iridescent matter is produced by the mollusk layer after layer, is itself a concretion of time arising from the soft and comforting inside of the shell, whereas its outside will sometimes have a rough and defensive outline. With Stéphanie Saadé, the use of precious materials always underlines a passage, or an ephemeral state which should be fixed. In Travel Diary, the gold follows the folds and creases of travel documents. On the surface of Identity in Change a silver leaf covers a photographic portrait of the artist’s taken a little before the exhibition, which temporarily reflects the face of who looks at it and substitutes herself/himself to this hidden identity. More than fetishizing individual traces, these gestures greet other presences, implementing the already mentioned estrangement from self, so that other lives are reflected in them.

Last but not least one must evoke the way that Stéphanie Saadé associates, like the two sides of the same medal, the notions of habitat and of fleeting. One will think of it in front of the precarious and empty nest of potter wasps which she found in the family house (Habitation). Or if one notices the shine of the diamond of Thin Ice, the maternal earring discreetly inlaid in the floor of the gallery. Each of her objects, however different, suggest an abandon, a loss, the part which one leaves behind when departure occurs. One should never confuse, in fact, running away and stepping aside, escaping and disappearing. Let’s then look at this “reunion with unknown friends”, with its caring proximity, like a reunion where each story emancipates, frees itself in order to claim the trivial persistence, inside every path, of the wounds which found of our common identities.

Franck Balland

1) Tristan Garcia, Nous, Editions Grasset et Fasquelle, Paris, 2016, p. 173.

2) Camille de Toledo, Aliocha Imhoff, Kantuta Quiros, Les potentiels du temps, Manuella Edition, Paris, 2016.

table, chaise, laiton

© Gert van Rooij

moulage en or 24-carats d’une lentille, lentille originale ayant servi au moulage, assiettes, tiges métalliques

moulage en or 24-carats d’une lentille, lentille originale ayant servi au moulage, assiettes, tiges métalliques

document de voyage usagé, or 24-carats

21 x 29,7 cm

© Gert van Rooij