Anatomies of Az-zahr: Stéphanie Saadé and the Dices of the Unmeasured

Stéphanie Saadé’s practice is concerned with fragmentation. Scattered traces conjoin into other sets, forming works of insistence that remain indestructible through dispersion. The subterranean scene takes place after the explosion, when all the cameras have turned away from the event, when those who were greedily preoccupied with their observing eye have already moved on to another ‘happening’. And so begins the story of the ungovernable, of indestructibility .

Saadé’s traces are abstract. They are neither traces of anything nor of anyone—they are dust, debris, waste. The saturation of the surface through accumulated debris produces a threshold effect which, due to the very materiality of reassociated fragments and their multiplication, escapes the artist’s control. In this sense, Saadé’s work is closer to Abdelkebir Khatibi than to Jacques Derrida or Roland Barthes, both of whom were Khatibi’s readers and interlocutors. The visual writing in question is what Khatibi calls intractable difference, i.e. that which first and foremost resists military and imperial destruction. The ‘trace’ is without potential for renewal . We don’t give ourselves a textual archive whose process of signification could be taken up again indefinitely. Meaning has already been interrupted, and there is nothing left to quote. We are no longer left with textual archives, but dusty surfaces that echo fingerprints on a screen instead. Something takes place beneath language, before poetics and in the interstices of writing. The fragment is neither a point of departure nor a point of arrival. It is what is conjured but never abolished by an artistic system of tracing, one that never becomes a totality. A system-fragment, then, in Schlegel’s words, which in Saadé’s work takes on dimensions unknown to German Romanticism. Saadé’s gesture creates a system at the heart of what the second half of the twentieth century saw as its destitution.

If this is anything other than yet another deconstruction, it’s because Saadé writes in order to stop writing. She writes time—letters for seconds that are minutes, hours or years. Substituting the alphabetic unit for the numerical, she creates a disturbance in measurement. Time is measured by duration, i.e. by time lived and expressed through language. There couldn’t be a more anti-Bergsonian experience, since the spatialization of duration creates an alternative measure—an inordinate writing of time through language that is made visual. In this game of love and chance, writing becomes something other than itself. It is visualized and thus becomes an image. It becomes something other than a text or a voice. Time is spatialized as much as space is temporalized. Duration is made space, without measurement translating time into something other than itself, since it is insofar as it is lived that a second can be an hour, a day, a month, or a year. The letter is an instant of lived time, an instant that is unbounded—an anti-number or an anti-measurement.

Here, an anatomy of time would coincide with an anatomy of language. Hence the use of calligrams, i.e. visual poems or poetic drawings. Writing in drawing is not calligraphic. Space-times are literally woven, embroidered on the threads of duration, on the clothes of passing seconds and hours. The torn flap of a garment is the opening onto a possible world once the act of fighting against the forces of destruction finds its own strength. This pre-poetics of contingency is not Mallarméan. The etymology of chance is an Arabic word, probably Andalusian—az-zahr. It refers to a flower as well as a dice to be played. What could have been something else instead takes on the form of a game. Mallarmé would not exist without Andalusia and the Arabic language. Saadé reconnects with az-zahr . Chance is put into a system because az-zahr opens up an infinite number of possibilities before our eyes. But there would be no anatomy of time if duration wasn’t a kind of animal or vegetal, in other words an organism. It’s true that the flower gives us an idea of time. It is as old as Aristotle. When Aristotle says that time is the measure of movement in his Physics (350 B.C.E.), he does so with the idea that movement entails the movement of living things. Physis was biologia. If the flower seems to be the opposite of the dice—its antithesis as an image of an ordered creation that reminds us of the intentional authority of a creator—then the organic or vegetal thrust is a necessity that can always be interrupted. The flowers of the az-zahr are the dice that can’t be abolished .

This cosmic constellation is cosmopolitical: it reminds us of what people keep forgetting and covering up. It says that what makes me think of you is not what makes you think of me—a work of dissymmetry that reminds the viewer that the privilege of oblivion is not given to those who never cease to escape destruction. Its debris doesn’t constitute a ruin. Scattered about, it persists and never ceases to enliven itself again. The insistence of elements previously thought to have been destroyed bears witness to a life that eludes all annihilative attempts. A port may explode, but the broken glass that remains claims the right to live elsewhere, transfigured by an artistic gesture that holds up a mirror to our inattentiveness, all the while affirming that no force, no state, can reduce a multitude of space-times to nothingness.

Mohamed Amer Meziane et Anissa Touati

November 2024

translation by Edwin Nasr

Anissa Touati and Mohamed Amer Meziane collaborate at the intersection of curatorial and philosophical practices. Touati, a transnational curator and researcher with a background in archeology and medieval history, develops a project on “Entangled Legacies of Space” at Brown University. Amer Meziane, a philosopher, intellectual historian and performer, has taught at the Sorbonne and Columbia University before joining Brown University as an assistant professor. He is the author of two books: The States of the Earth and Au bord des mondes. Together, Amer Meziane and Touati explore correspondences between artistic and conceptual practices through symposiums and performances.

Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard

Stéphanie Saadé

2024, video

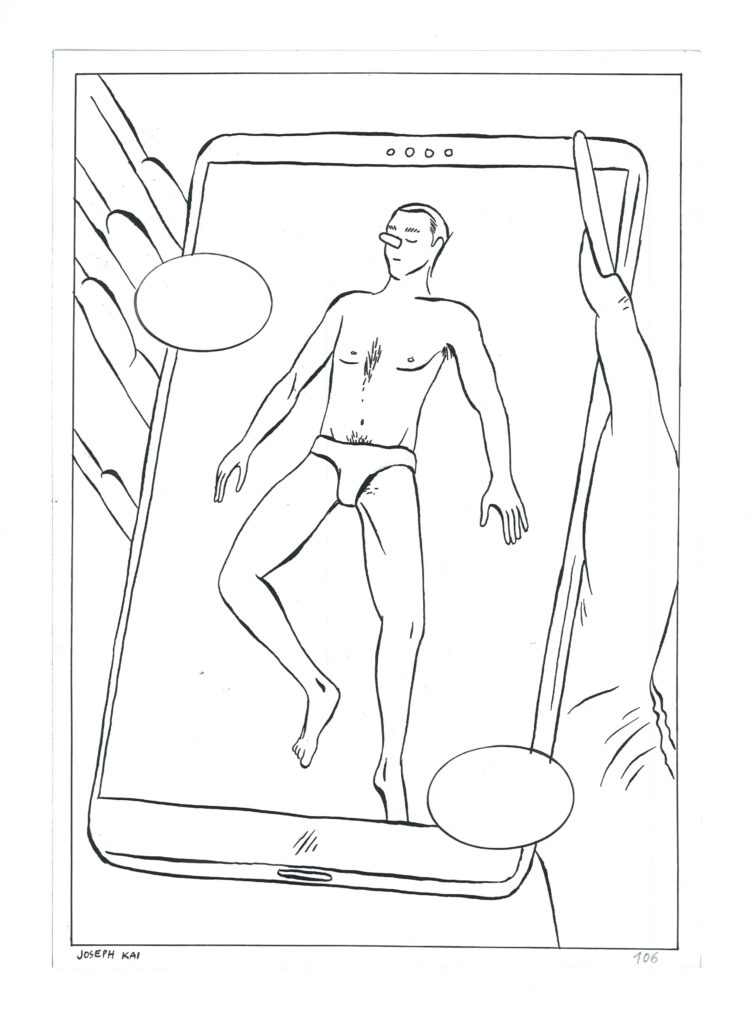

To coincide with her exhibition, Stéphanie Saadé has invited Lebanese comics artist Joseph Kai to present original plates from his first graphic novel, L’Intranquille (Casterman, 2021), published in English as Restless by Street Noise Books. It follows Samar, an artist living in Lebanon, and examines his anxieties, desires and dreams at the heart of one of the most tumultuous periods in the country’s contemporary history.

Since 2010, Joseph has been part of the Samandal Comics collective, first as a contributor, then as editor: Geography (2015), 3000 (2019) and Cutes, récits queer et trans* (2022). Recently, his work was exhibited at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, and in 2022, he presented his first solo show, I Never Asked to Be So Sad and So Sexy, in Brussels.

In 2024, Joseph received the Mahmoud Kahil Prize for Arab Graphic Novels and the Bourse Découverte from the Centre National du Livre.

Excerpt from L’Intranquille, Joseph Kai © Casterman, 2021

page 106, 29.7 x 21 cm

Black ink on 200 g/m2 paper