Every week, an artist of the gallery will share his passion for the work of either a film maker, such as Maurice Pialat from whom we have borrowed the nice title of his film (made in 1983), or a musician, a writer, an artist.

Alun Williams

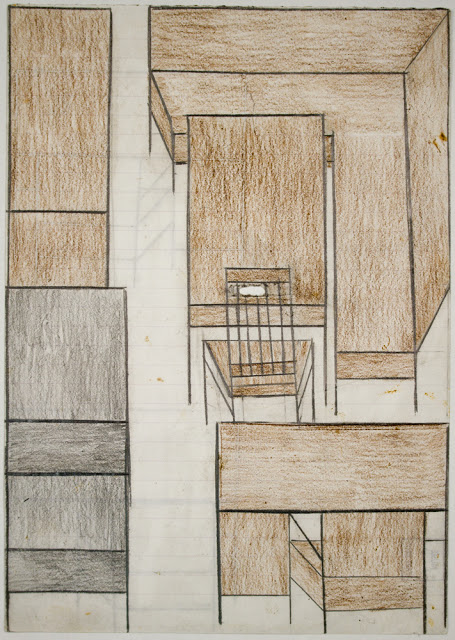

Alun Williams, Jules & Victorine Hotel, oil and acrylic on canvas, 71 x 56 cm, 2010

I would like to return once again to the story of Victorine Meurent, whose name is too easily reduced to her identity as Manet’s favourite model, and the main character of his revolutionary paintings, Olympia and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe. It’s true that it was thanks to these two that she became a Paris celebrity in 1863 – the genuine symbol of the liberated woman of nineteenth century Parisian “modern life”. Thanks to Manet’s paintbrush, and in a blatant challenge to the conventions of the academic nude, Victorine took off her clothes and glared at the spectator with defiance and a thorough lack of reserve. It was a real scandal at the time, and if notorious Manet was mounting an attack on the conventions of art, through these pictures notorious Victorine firmly slapped the ubiquity of masculine dominance in the face.Indeed, if we see Victorine in the context of her highly patriarchal and macho times, it isn’t difficult to consider her achievements and courage as having at least as much merit as those of Manet, whose birth conferred him with every advantage! It’s very clear that Manet is a seminal artist of the period – one of the true precursors of modern art, but despite being born into a prosperous and well-connected family, his attempts to have his work accepted and recognized by the prestigious official Salon almost always failed. Of course this can be seen as proof of the greatness of his avant-gardism, but I’m tempted to say that Victorine is just as audacious for squaring up to the multitude of obstacles that confronted a woman seeking to exist as an artist in the late nineteenth century!Coming from a modest background, at a time when women were barred from entering the École des Beaux-Arts and had to pay high fees to study in a master’s studio, Victorine very rapidly and almost entirely on her own, achieved the exploit of regularly exhibiting in the Salon! This does show that she clearly had certain talents. Each period chooses its experts who judge was is valid according to established criteria, and it’s clear that Manet corresponded to the criteria of the following period which he himself helped ultimately helped to formulate. But this doesn’t mean that the preceding experts were not capable of recognizing certain undeniable qualities of painting.

With hindsight, it’s extremely easy to say that the Salon committee was blind to the qualities and potential of the avant-garde, and that Victorine’s work was simply well executed and conventional. Existing criticism of Victorine’s work is rare and mostly written well after the events. Almost half a century after the Salon of 1876, Manet’s biographer, Adolphe Tabarant wrote in his “Bulletin de la Vie Artistsique” in 1921 (six years before Victorine’s death): “To the Salon, she sent her own portrait, followed by historical and anecdotal paintings. Sickly artsy frivolities! What was the point of her living in such proximity with a Manet?”[1] I sincerely hope that poor Victorine, who was 77 years old in 1921, didn’t have the misfortune to read these pathetic lines.

Victorine continued to refer to herself as an artist until her death in 1927, and it’s true that she sometimes tried to use the notoriety of Olympia to advance her artistic career, as when she had a series of cards made to promote her work on which was written : “Victorine-Louise Meurent Exhibiting artist at the Palais de l’Industrie. I am Olympia, the subject of the celebrated painting by M. Manet. Please observe this drawing. Thank you!”[1]There are perhaps some undertones of despair here, but less than in the story of Parisian outings some years later, when Toulouse Lautrec derived mischievous pleasure from bringing Victorine along with him to society parties primarily to make a grandiose entry saying: “Allow me to introduce my friend, Olympia!”

Weary of the company of men and the insurmountable challenges facing the few women artists, Victorine withdrew to Colombes where she lived the last twenty years of her life with a certain Marie Dufour. The two friends died just three years apart, in 1927 and 1930. A report mentions a large bonfire prepared by the bailiffs in order to dispose of the contents of the house. Neighbours described the burning of easels, musical instruments and canvases…

In the end, Victorine did achieve her ambition of having a place in Art History. In my opinion Picasso was fascinated by her strength of character, and not simply by Manet’s famous painting when he painted Victorine numerous times in his déjeuner sur l’herbe series. I myself have been pretentious enough to produce a series of paintings in which I imagined love affair that Victorine might have had with Jules Verne (he also became suddenly famous in Paris in 1863). The series is an homage to “Jules and Victorine” along with Manet and Picasso.

Only four paintings by Victorine are known to exist today. Three are held in the collection of the City of Colombes. The fourth, her self-portrait from 1876, apparently rediscovered and authenticated very recently, shows much quality and a defiant look painted thirteen years after that of Olympia. It’s satisfying to note that this painting is far from being a “sickly artsy frivolity”, to such an extent that some have already suggested that it must have been retouched by the hand of Manet himself.[2] In the end, it’s exasperating to hear yet another attempt to undermine poor Valentine’s talent, almost a century and a half after she painted this self-portrait!

While this discovery is undeniably exciting, it makes it even more frustrating to know that so many of her paintings and drawings have disappeared. There must be others in existence somewhere…Take another look in the drawers and attics of your Parisian grandparents!

November 2020

[2] Adolphe Tabarant, “Celle qui fut “l’Olympia de Manet”, unpublished manuscript, 1948, p. 66

[2] Laurent, E., “Mademoiselle V, journal d’une insouciante”, Paris, La Différence, 2003, p. 225

Victorine Meurent (Paris, 1844 – Colombes, 1927), Autoportrait (détail), Circa 1876,

oil on canvas, 35 x 27 cm

courtesy galerie Edouard Ambroselli, Paris

Ramuntcho Matta

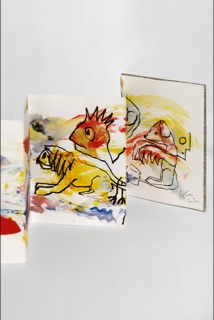

Ramuntcho Matta, (détail) Entre Chien et Nous, encre et aquarelle sur papier, 17 x 12 cm / déplié 17 x 150 cm, 2020

Ah my loves…

My loves my loves my loves

A perpetual echo in everyday life

there are the loves that remain, and the loves that pass and remain as well.

and then there is what you think love is and it’s nothing but hocus-pocus.

Besides, “love” is quite a recent term.

Not so long ago these rare relationships were called “sincere friendship”, it was neither possessive nor exclusive… but that’s another story.

The story here is the stories that accompany us.

such painting is a moment… an uplifting punctuation of a unique stay.

Dürer’s rabbit… in Vienna…

and stories are relationships.

It starts with Mom, for Jazz which is as much a “work” as a meal or a visit to an artist friend’s house.

And of course the studio has a great impact on you.

With Dad it is rather the weekly visit to the Louvre to see ONE work and one work only.

At the Louvre or at the Museum of Man or at the « Porte Dorée ».

In my personal construction I rather favor relationship.

relationship to the world above all, relationship to others…

A relationship to a certain kind of morality, to a certain kind of ethics.

to the principle of responsibility.

and this responsibility is honesty.

a dog is always honest.

it is what it is.

yes there is deceit, lies and everything that makes a being alive.

You do not ask a dog to justify itself, you do not ask it where it went.

There is « Beneath the Underdog » of Mingus , my life as a dog of Boulgakov…

my love is the dog

the dog has seventy thousand times as many perceptions as we have, not two or ten or a hundred.

Seventy thousand more sensors than us.

And some people have something of a dog in them.

That is what I love

The dog

first of all in Asger Jorn who states that the most precious thing in the human being is the animal, and for (him, for me ?)it is instinct.

You do not paint: you are the paint.

and beauty is not aesthetic: it is ethical: it is the truth, it is what is raw, what is unfiltered…

what is funny as well.

It was Asger who invented the international situationist , afterwards Bobord wasted away this initiative.

and as my subject is not this or that painter, but the dog there is sometimes in us, here is another one who has another type of dog in him

Oyvind Fahlstrom.

For him, the subject is the real.

The subject is not the artificial real, but the inner effects of a much superior real: that of the sensible, and of the infinite.

to be in it like a dog.

to be in it like a dog?

a dog is everything but a slave.

a dog is absolute empathy.

and Oyvind hears the world and tells it in boxes, lines, games and situations.

He invites everyone to develop multiple selves.

without ever forgetting: the political self; the one who acts on the world, through the way he rubs shoulders with the summits…

and then here is another one who has something of a dog:

Robert Motherwell.

Bob stops.

He stops reality and shows its different layers.

He gives free rein to our flairs.

he awakens our sensations

and beyond the dogs there are the bitches

I did not start with them because I did not want to be misunderstood.

First of all, there is Alice Liddell, without whom there would be no Lewis Caroll.

is it necessary to produce things at all costs or to produce a life first?

Then Nina, without whom there would be no Charles Cros, who was the first to hone them.

Then Carol Rama who dares everything.

and Dorothea Tanning

and the list is too long…

you will have guessed.

I have « loves » and not “one” love.

It’s my musical side, I can’t stick to a single scale.

I am a polygamist.

Each love enriches my perceptive palettes

and I, in turn, try to be up to the task, true to my own way

Like a dog

and like any good doggie

I do my business where I am told.

Ramuntcho Matta

November 2020

Ramuntcho Matta, Entre Chien et Nous, encre et aquarelle sur papier, 17 x 12 cm / déplié 17 x 150 cm, 2020

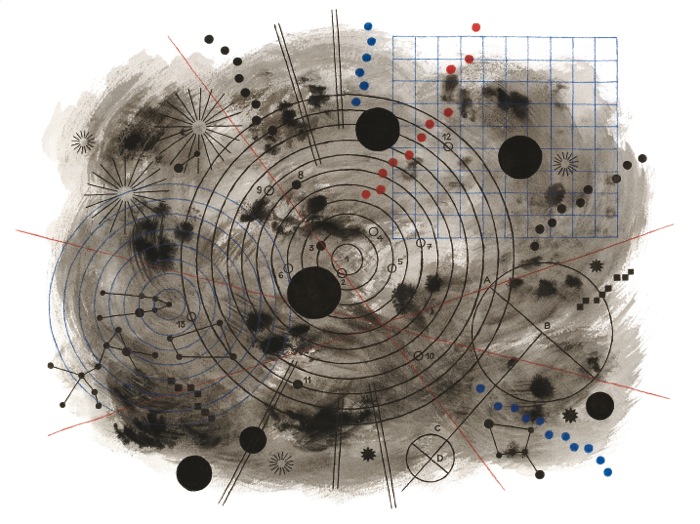

Jochen Gerner

Alexander Cozens (1717-1786)

I have discovered Alexander Cozens, a British artist, through his experimental drawing method: A New Method of Assisting the Invention in Drawing Original Compositions of Landscape, 1785.Starting from random or accidental black ink blots of which he prolongs lines and invents forms composing a recognizable landscape, he thus passes from total abstraction to a subtle figurative representation.

This principle of avant-garde experiment seems to me totally new in the 18th century.Alexander Cozens made paintings reminding one of 17th century landscapes, and drawings anticipating both Victor Hugo’s random exercises (19th century), and the drawings of the 2Oth century modern currents, from Cezanne to Joan Mitchell.

Abstract blots, supple lines, cloud, foliage and rock studies, Cozens developed a complete catalog of infinite drawing possibilities.

Classic, romantic and modern, he balances between figuration and abstraction, a classical school and a radical avant-garde current.

Working with coincidence, temporality, oubapian experiences and constraints, on printed aids or facing reality, I notice my constant and ever renewed attachment for Alexander Cozens’ work.

Jochen Gerner

November 2020

To discover the work of Alexander Cozens click on this link:

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/cozens-the-cloud-t08057

Jochen Gerner

Cosmos, 2016

India ink and pencil on paper

35 x 46,5 cm

Guillaume Pinard

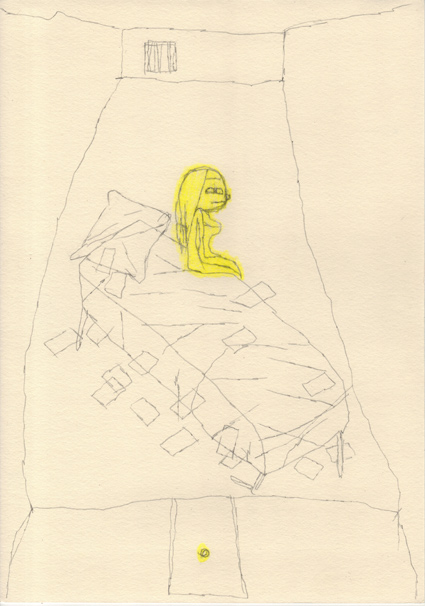

We are pleased to open this new chronicle with a text of Guillaume Pinard about the work of Hélène Reimann, born in 1893 in Poland.

Guillaume Pinard, Hélène, graphite et crayon, 21 x 29,7 cm, 2020

I no longer know what the hypothesis of an existential vacancy, of the floating and invisible practice of writing, drawing, or music – what else – is worth, in a system in which we valorize the slightest action and ask for adhesion or immediate valorization. I no longer know what this movement, that stood for the idea of an unproductive and emancipating form of thought, is still worth, this gratuitous leap into the elaboration of subjectivity, when the precariousness of intelligence is industrialized and when all artistic, intellectual productions are handed over to commercial firms.

I no longer know what an idea, a work of art, are worth when they are not even goods, but a simple piece of data among others, meant – like a data recorder – to capture, locate, trace the attention of an Internet user in the ocean of clicks. I no longer know what the images of a catalog submitted to opinion poll rather than to the examination of their contents. And yet, I enjoy nothing more than this broadening of the visible, nothing as much as the exhalation of possibilities and the multiplication of prescribers; and I still want to participate. Now what?Hélène Reimann (1893 Breslau/ Poland 1987 Bayreuth/ Germany) was the mother of seven. She sold shoes in a shop. Schizophrenia gradually condemned her to repeated stays in psychiatric hospitals. Thanks to one of her daughters, she was protected and escaped the Aktion T4 plan (the campaign to annihilate physically and mentally disabled adults) of Nazi Germany.

From 1949 onward, Hélène Reimann was permanently confined to the psychiatric hospital of Bayreuth. There, she spent most of her time drawing. She would draw all that she was now deprived of and which she did not want todisappear: clothes, shoes, interiors, furniture, a few animals, portraits, and flowers. All the drawings of her we know today were made between 1973 and 1987. From 1949 to 1973, the hospital staff had orders to find out and destroy all the drawings Hélène Reimann made and hid under her mattress, in her sheets and under her pillow. It took the arrival of Professor Boeker at the head of the establishment to let her keep the works she created. So tirelessly, Hélène Reimann maintained – against the coercion of the institution in which she was supposed to be cared for – her drawing practice for 24 years. Nothing and no one was able to stem the need for this woman to reconstitute the theater of her memory.It is perhaps too simple to use Hélène Reimann as a counterpoint to the overexposure and the commercialization of the objects of thought, as the radical example of resistance to norms and institutional standards. I will be objected that Hélène Reimann did not participate and never participated in the “art game”, that she had no artistic ambition, no plastic research, that she probably never took a critical look at her drawings or her confinement, that she was simply insane. Perhaps, but the black diamond of the life and resistance of this woman, her burning connection to the act of drawing, the subversive strength of her deed compel us to regard her drawings as the sparks which sparkle and lighten the abyss of a being tormented by the world, and rise up against this world.So, confronted with Hélène Reimann and even if it means to play roulette with algorithms in order to flatter our existences or the economy of our creations, even if it means plunging into the brackish water of the networks and their undifferentiated markers, we must be adamant and bound to estimate everyday what deserves or not to be hidden under the pillow.

Guillaume Pinard

October 2020

Hélène Reimann, Funiture, before 1987, graphite and crayon on thin lined paper (the same as letter pads), 29,5 x 20,8 cm.

Villeneuve d’Ascq, LaM © Credit photo : N Dewitte / LaM