Anne Barrault Gallery is pleased to present Jagdeep Raina’s first solo exhibition in Paris. The young Canadian artist will present a set of new works, comprising embroideries and drawings.

The plurality of history is a main subject of Jagdeep Raina’s works. His family, from the Kashmir region bordering the Punjab, emigrated to Canada in the ‘60s due to the unstable political climate following the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947. The departure of the British authorities from the region led to its violent division into two independent nation-states, along with huge displacements of people on both sides of the new borders and beyond.

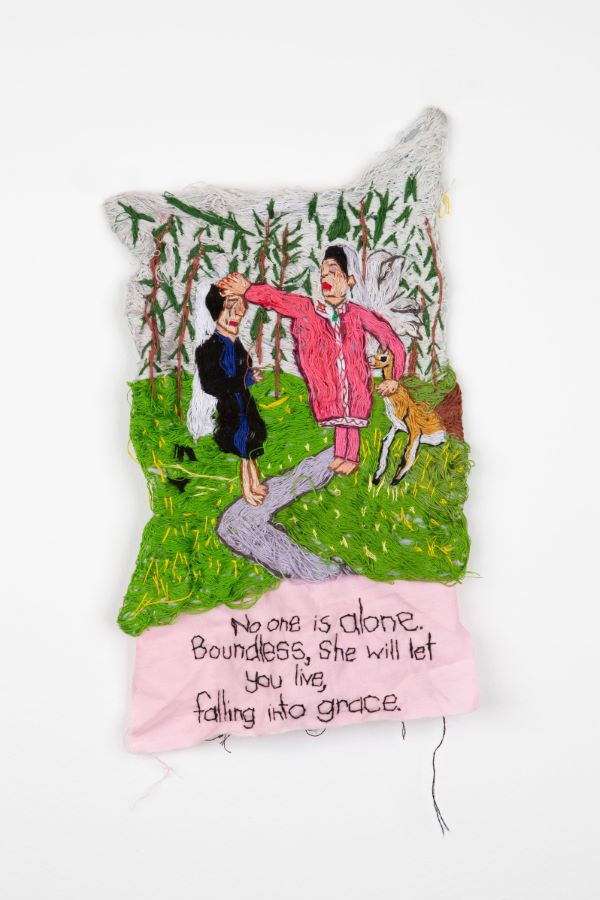

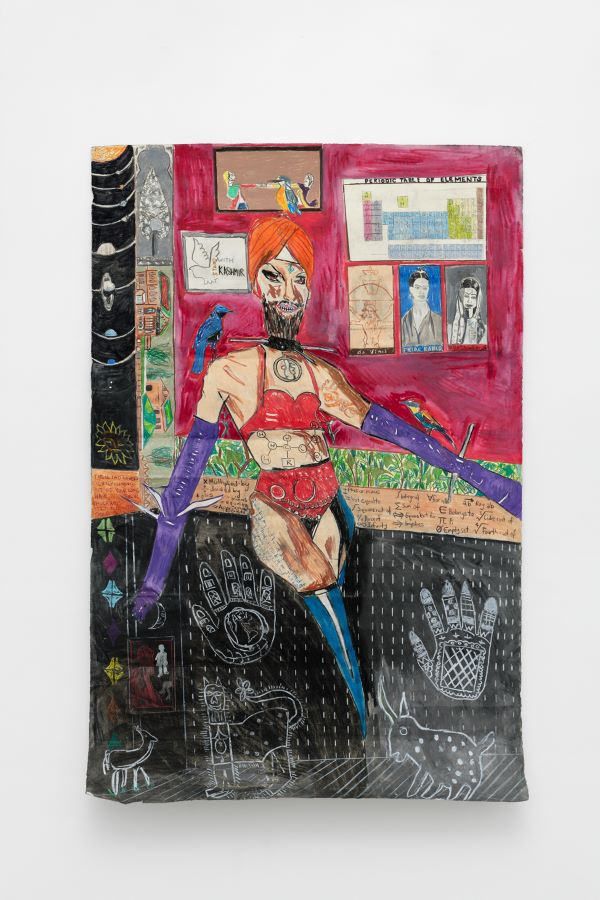

With his interest in various textile techniques (Kashmir and Punjab embroidery, shawls, phulkari) Raina reconnects with and revives an ancestral heritage, which nears disappearance today. Additionally, the techniques of textile arts have long been activities practiced by women, and they are still very gendered. This reorganization of historical configurations shows Raina’s wish to question repressive orders, while revealing the divisional hierarchy at work with gender, class, caste, race, sexuality and geography. Raina’s practice therefore implies tradition and transgression in equal measure. In creating his works, he draws inspiration from historical and informal photographic sources he finds or produces himself. With fluid and malleable materials like embroidered tapestry, writing, drawing, ceramics, animated videos, and more recently 35mm film, he uses reproduction and reappropriation strategies to disrupt the archives of permanence. Raina questions the intimate relationships between personal and public archives, emphasizing that which links us to history, to understand narratives that are beyond us.

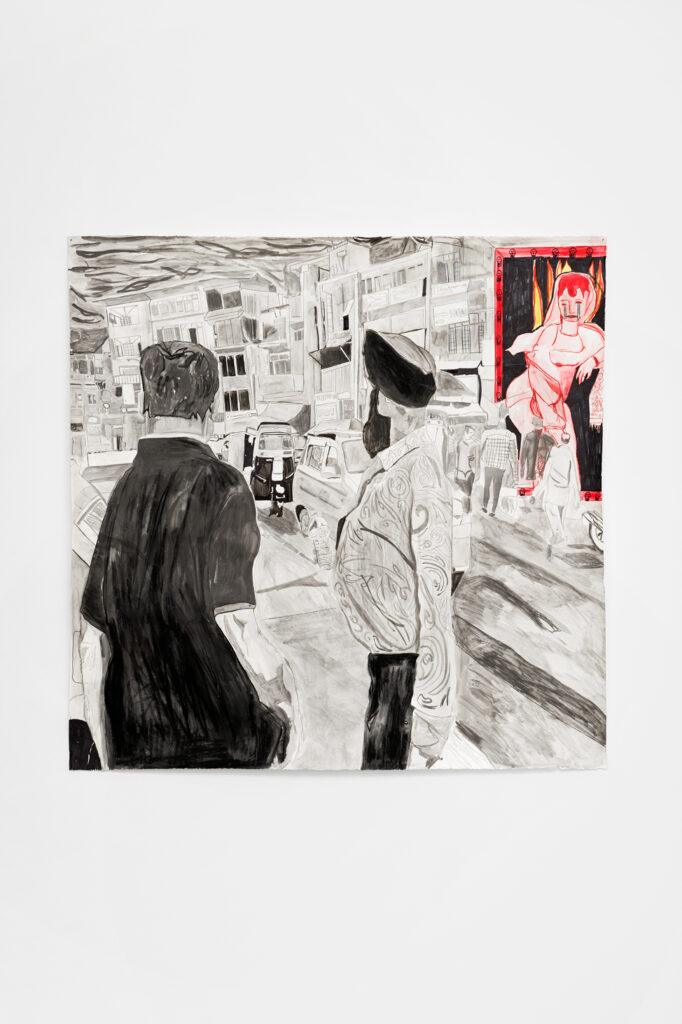

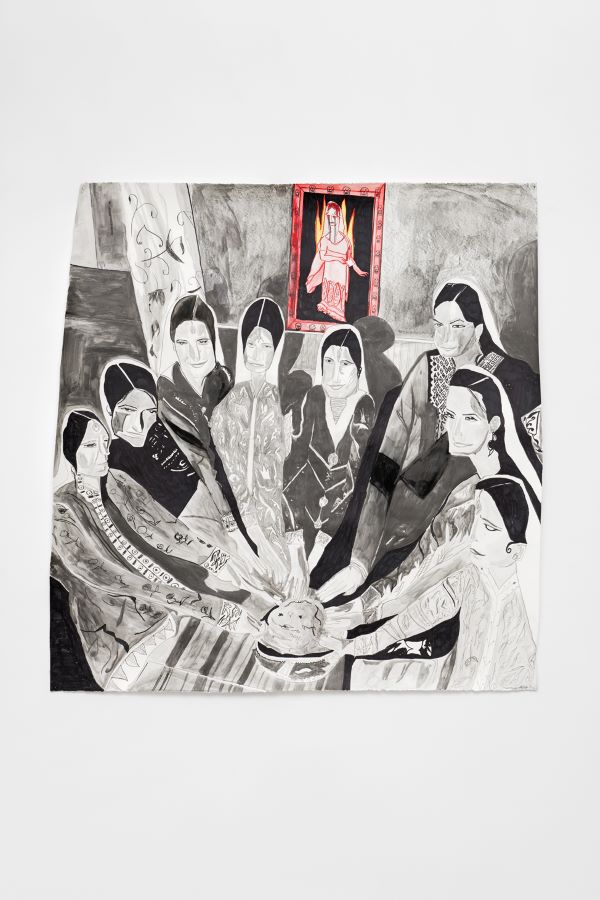

For his first exhibition in France, Raina wishes to confront the country with its orientalist and colonialist past. The Kashmir shawl, brought back from the Egyptian campaign by French soldiers in 1798, became Josephine de Beauharnais’s favorite toilet requisite, then Marie-Louise of Austria’s, as well as Madame Rivière’s, whose portrait by Ingres in 1805 features one of these shawls in the foreground. The Kashmir shawl became a luxury item of clothing and was in fashion for most of the 19th century, until the trend decreased and left the workers of the region without resources. If Raina wants to refer to the violent modes of the exploitation and commercialization exerted by France at the time of the production of the fabrics of the day, he also sets up some kind of resistance. In a series of six drawings composed with a quilting technique, one can notice a Kashmiri woman entering a Kashmir textile store to have a hand-sewn, woven and embroidered coat fitted. She is seen posing while laughing warmly with the saleswomen. This scene does not depict a specific place or moment but rather has the effect of a dream. This fantasy is powerful, because it creates an inversion by suggesting an alternative scenario in favor of those who have been exploited and abused. The re-appropriation of the traditional Kashmiri garment as an item of costume and protection is part of this metaphorical reconquest of the territory, which is a recurring and moving theme in the artist’s work.

Elsa Delage

Jagdeep Raina, Towards the valley, exhibition view

(photo Aurélien Mole)

Lush green gardens are blooming colourful flowers with snow capped mountains as the backdrop . The air, fresh and crisp. Lavish houseboats line the river bank, with luxurious interiors that include hand crafted wooden furniture, large chandeliers that hang in each room, hand woven silk rugs that cover the floors, and opulent lamps that fill each room with warmth. The Verandahs pull in the beauty of nature, bringing it just that much closer. Allowing you to be both observer and participant. Nature is harmonious, free flowing and never forced.

The Climate in Kashmir is unique as it experiences all four seasons, adding even more wonder and dimension to its already diverse landscape. Kashmir’s natural beauty expands to all facets of life there, from their rich culture, intricate hand woven tapestries, shawls, and silks, along with their flavorful cuisine and spices but mainly the beauty and optimism of the Kashmiri people. Celebrations and gatherings show their vibrant way of being. Kashmir, unfortunately has another backdrop: decades of war and conflict that still exist today. The stark contrast from the natural beauty of the land and years of military occupation. Depicting the true resiliency, strength and beauty of the Kashmiri people, that still shines through.

What are the connecting fibers that make up the cloth of Kashmiri culture and lifestyle? Connecting both past to present, tradition to innovation. In a rapidly changing and growing world system, some things remain constant. Traditional crafts and art forms such as weaving, needle work, embroidery, wood carving, cannot be rushed and every step is integral to creating the end result. Jagdeep’s quilts depict a woman in a traditional Kashmiri sewing atelier being fitted for a hand embroidered, hand sewn and hand woven coat. In the series of quilts we see the woman connected to every step of the process. This coat is called a Choga or Pheran which functions both as an artistic creation and utilitarian purposes of covering and protecting the body. The Atelier is a safe haven filled with warm lighting, traditional handmade artifacts representing heritage, home and belonging. The quilts are all purple, a color once reserved only for royalty and the elite class, representing the epitome of luxury.

Couture fashion houses around the world are known to house only the finest of garments, creating new cutting edge designs as well as reimagining familiar classics. These designs embody not only the vision and values of the fashion house but also the ever changing socio/economic and political climate of the time. In contrast, the Kashmiri Choga’s and Pherans date back to the 16th century, remaining unaffected. Kashmir and India at large are unique in the way that it so effortlessly holds onto tradition all while embracing change brought on by globalization.

In the west, custom made, tailored one of a kind couture designs are normally only accessible for the wealthy, as the cost of getting anything handmade can really add up. This is not the case in India where most people have their own tailor, a tradition dating back to many centuries ago. The process of creating a garment for an occasion or event is very personal, working with the tailor to choose the fabric, then working together to create a design and customizing the fit.

The south asian diaspora holds on to pieces of these traditions, whether it be artifacts, photographs, and garments, as a reminder of who we are. My mother had an interest in sewing and hand embroidery. At the age of 15 she started sewing bedsheets and pillows with hand embroidered floral motifs . She would also make hand made shawls and rugs. She sewed and hand beaded her own wedding shawl and chunni, which she has since passed down. Growing up I remember her sewing most of our clothes. As an immigrant mother now living in Canada this was not only cost efficient but also brought us great show and pride. Our history, ancestry, and shared experiences follow us everywhere we go. Our identity is complex and layered. There is generational trauma, years of pain, struggle and oppression. But there is also beauty in the humble resilience of our people and our relentless optimism. Collectively these create the cloth that is our identity, the very fiber of our being. Each one of these fibers intertwines to create something truly beautiful.

Pardeep Bassi

Jagdeep Raina

Kashmiri birds, 2020

Embroidery on muslin

35,6 x 25,4 cm

Jagdeep Raina

The last bits of thread, 2023

Mixed media on paper, sewn with bordered fabric, batted, basted, binded into a quilt

101,6 x 91,44 cm

Jagdeep Raina

Adorned in her Mango shaped choga, 2023

Mixed media on paper, sewn with bordered fabric, batted, basted, binded into a quilt

91,44 x 101,6 cm

Jagdeep Raina, Towards the valley, exhibition view

(photo Aurélien Mole)

Jagdeep Raina

The edge, 2023

Embroidery on muslin

30,48 x 17,78 cm

(photo Aurélien Mole)

Jagdeep Raina

Beautiful weaver, 2020

Embroidered tapestry, Kashmiri Ambi on Cotton

50,8 x 20,3 cm

Jagdeep Raina

Boundless, 2023

Embroidery on muslin

33 x 18 cm

Jagdeep Raina

Inderjeet, stay with her, 2020

Embroidery on muslin

55,9 x 22,9 cm

Jagdeep Raina

Madame Rivière, 2023

mix media on paper

127 x 127 cm

(photo Aurélien Mole)

Jagdeep Raina

Josephine, 2023

mix media on paper

127 x 127 cm

(photo Aurélien Mole)

Jagdeep Raina

Good Luck, 2023

mixed media on paper

101,6 x 66,04 cm