“Topor is probably the greatest graphic mind of the twentieth century.”

Seymour Chwast, the co-founder of Push Pin Studios.

The exhibition curated by Alexandre Devaux at Anne Barrault Gallery presents a set of works by Roland Topor done at different periods and with several techniques. Ink drawings, crayon ones, linographs, lithographs, drawings painted with a spray or a brush, photographs called “photomorphoses” will enable the visitors to grasp the range of this artist’s graphic and polytechnic genius, who was an avant-garde all by himself.

Roland Topor was born in 1938 and died in1997, in Paris tenth district. His work is rich and diverse and protean. An illustrator, a writer, a multitalented artist, he was published in French and foreign papers : Bizarre, Hara-Kiri, Elle, The New York Times, Le Canard enchaîné, Libération, Le Monde, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and so on. He wrote books, he illustrated the works of more than a hundred writers, among them Boris Vian, Marcel Aymé, Félix Fénéon, Tolstoï, Georges Sand, Pierre Benoît… He conceived the scenery and dresses of several plays and operas for Liget, Penderecki, Savary, and others. He wrote film scenarios, plays, songs, tales, novels, and short stories. He acted in William Klein’s, Raoul Ruiz’s, Volker Schlöndorff’s films. He made animated cartoon films such as Fantastic Planet. He took part in many radio and television creations. Among others, he is the author of the programme for children Téléchat, and the co-author of Merci Bernard and Palace. The creator of Panic Movement with Fernando Arrabal, Jacques Sternberg and Alejandro Jodorowsky, Topor had links with several movements and “artist families”, such as Cobra, the Situationist International and Flexus. His drawings and paintings have been shown many times and are owned by several private and institutional collections, among them: Pompidou Centre, Strasbourg museums, the Stedelijk Museum, Warsaw Fine Arts museum, Munich Stadtmuseum, and others in Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Sweden, the United States…

Roland Topor started to be known as a press illustrator, the way, for him, of “rubbing shoulders” with life and distancing himself from the accursed artist he could have been if he had remained the painter everyone wished to be. Thanks mainly to drawing, and writing, Topor has been able to create the vocabulary of his thoughts. Topor was a thinker, but an active thinker. He was a thinker whose weapon was a pen; a thinker able to examine the world and to examine himself; a thinker who dared oppose the paradoxes of his imagination, the product of the clash between his awareness and his unconscious, against the consensus of the market, politics, society and culture. Few are the artists who can rise and go down inside their minds. Few are those who manage to translate what they have seen in man, the good and the bad points, inside their own heads.

A double-sighted gift which each of us could have, but which we give up, was but child’s play for him. “I exploit images, concepts and genres”, he says. Like Evguénie Sokolov , the hero in Serge Gainsbourg’s tale, Topor was able to adjust the seismograph of his psychic tempests rather than suffocate to death with congestion, or repress any shameful entity according to a despotic superego. To become the master of such a game, you must be aware beforehand, that “to play is a way of making things less serious, while giving them another kind of gravity.” You have to be a genius.

In order to avoid the traps of conformity and overcome the easy way out, Topor has adjusted his rules of creation. Drawing is quick writing, maybe the quickest. But you must not trust the toil of the mind, so that imagination can bloom and give birth to wonderful or fascinating things:

“Pure imagination does not exist. If I were to define imagination, I would say it is rather a mixture of memories. It is the power, which, like in a dream, allows one to displace the hierarchy of the values, which dominate everyday life. What I draw is not completely invented. There are even some elements (an attitude, a gaze, the fold of a dress) that I pick up from magazine photographs, because I like the same drawing to be based on various intentions and techniques: a detail, precisely observed, will reinforce the strangeness of a situation; one part of the drawing can demand to be done slowly, another will be done swiftly, realistic rendering and stylization, flat wash and volume can coexist. My method? I look for a pretext to draw, an idea, which I often find through reading or looking at books. The most difficult is to find a reason to set to work. Afterwards, the impetus makes me do drawings the one after the other. The cohesion of this series of drawings will not lie in a theme, but in the period of time, quite short, when I did them, in a rather obsessional state, so that , in these moments, I happen to dream of ready-made drawings. My approach is mostly systematic. For example, I can begin with the idea of someone standing on one finger. I then multiply the possibilities; I look for analogies, contraries. It is like a game. I play the game with the finger: will the figure balance on a different finger? Will this finger belong to one hand? Etc.”

An exhibition of Gébé’s drawings will follow Topor’s, though entangled with it. There is a very strong link between these two brilliant artists

At the beginning of his career, Topor made illustrations for Bizarre magazine, so did Gébé.

Topor was introduced to the public by Jacques Sternberg through the weekly arts, so was Gébé.

Eric Losfeld and Jean-Jacques Pauvert were the fist to publish Topor’s illustrated books, as well as Gébé’s.

Topor did really start off well in professional life when he contributed to Hara-Kiri, so did Gébé.

Topor was one of the best in the renewal of graphic humour in France, in 1958, so was Gébé.

Hara-Kiri humour, at the height of its success, was mainly due to Topor’s contributions, as well as Gébé’s.

In May 1968, Topor joined L’Enragé, so did Gébé.

Topor was an illustrator who could also write, so was Gébé.

Topor wrote shorts stories, novels, plays, films, sketches for the TV and the radio, so did Gébé.

Topor took part in Tac au tac, Jean Frappat’ s television programme, in which artists vied with one another in inventiveness in graphic games picked up from the surrealists’ or Grand jeu’s literary ones, so did Gébé.

Topor read a lot, so did Gébé.

Topor drew a lot, so did Gébé.

Topor loved detective novels and the cinema, so did Gébé.

Topor was rather short, so was Gébé.

Topor is a great artist, because he is a great thinker, so is Gébé.

Topor liked hard drinks, so did Gébé.

Topor enjoyed smoking, so did Gébé.

Topor wrote many sketches for Merci Bernard and Palace programmes, so did Gébé.

Topor is a huge inspiration for many artists, so is Gébé.

Topor was born in 1938 , so was Gébé, but nine years earlier.

Topor died in April 1977, so did Gébé, but seven years later.

The pair Topor/Gébé is for me the most creative one in the world. They are two great conceptual, graphic, intellectual figures. Gébé plays with the conscious elements of reality. He plays, in the light of conscience, twisting the logic spring until your mind gives up, until absurdity. It is a little the same thing with Topor, in the darkness of unconscious or subconscious waters, and often without any word. Topor does not twist the spring; he states a fact right away when all the springs have given way. I imagine Gébé as a white “mass”, and Topor as a black “mass”. However, each of them, and each of their works is pregnant with its contradictory principle. The exhibition of Gébé’s drawings will appear in embryo at the time as that of Topor’s, to open in December at Anne Barrault gallery.

The text and proposition by Alexandre Devaux, an art historian.

The exhibition at Anne Barrault gallery starts when the books Topor, dessinateur de presse, published by Les Cahiers Dessinés, Topor Strips, published by Nouvelles editions Wombat, Gébé’s J’ai vu passer le bobsleigh de nuit, published by Les Cahiers dessinés, come out.

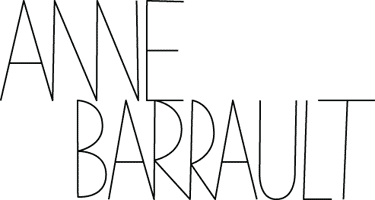

Épigrammes de Martial, 1986

dessin à la plume,

29,5 x 21 / 32 x 23,2 (avec cadre)

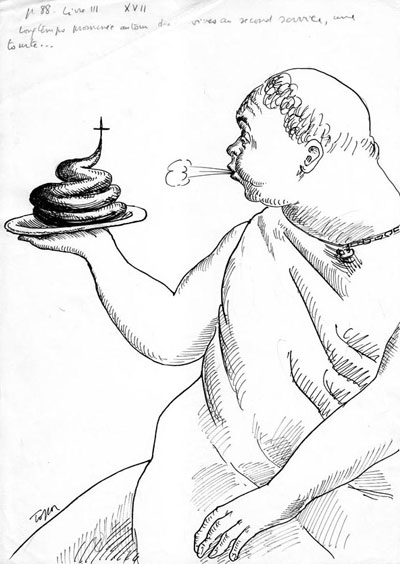

Épigrammes de Martial, 1986

dessin à la plume,

29,5 x 21 / 32 x 23,2 (avec cadre)